AHA! I’ve broken out The Fountain Pen again! It’s a relic from early in The Marriage, from a year when each of us was delighted, on Christmas Morning, to discover we had bought the other a pen. We were each going to be writers, you see.

Actually, come to think of it, this was before the marriage—what you could call the pre-marital honeymoon and cohabitation phase.

My Good Lord, were we ever so young?

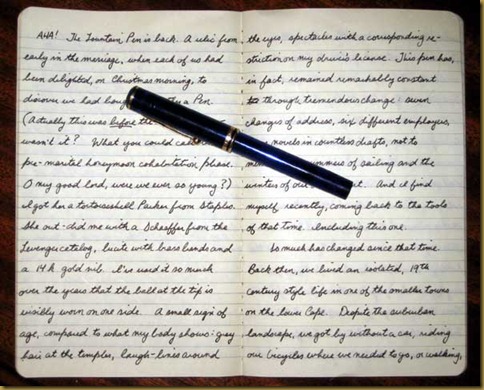

I bought her a tortoiseshell Parker from Staples. She out-did me with a Schaeffer from the Levenger catalog, a semi-translucent Lucite barrel with brass bands and a 14k gold nib. I’ve used it so much over the years that the tip is visibly worn on one side. This is a small sign of age, compared to what my body shows: grey hair at the temples, laugh-lines around the eyes, spectacles on the face with a corresponding restriction on my driver’s license. This pen has, in fact, remained constant through tremendous change: seven different addresses, six different employers, three novels in countless drafts, summers of sailing and winters on skis.

Now I find myself coming back to the tools of that time. Including this one.

While so much else has changed. Back then, we lived an isolated, 19th century style life in one of the smaller towns on the lower Cape. In a rebellion against the suburban landscape, we survived without a car, riding our bicycles where we needed to go, or walking if there was snow on the sidewalks. There was no Internet, not in the town where we lived, not at a price we could afford. What there were, were plenty of A.O.L. floppy discs coming through the mail, handy to re-format and use as backups for the WordPerfect documents I wrote on The Wife’s laptop, a machine that had cost her $3000 several years earlier, in college. (For several decades there, it seemed that a new computer always cost $3000.) This laptop was a revelation to me, as was the bubblejet printer that could output any font in any size—bringing home to me for the first time the full significance of the Kitchen Table Publishing Revolution. And then for some reason I never entirely embraced it. I wasn’t ready to abandon my Olympia and Remington desktop typewriters. (Later on I did abandon them, to my even later regret.)

We lived our lives in a sort of bubble, getting our news from newspapers purchased at the Superette a couple of miles away, or from the magazines we picked up at the Post Office just down the street from the Superette. Serious entertainment would come from the books we bought in binges from second hand shops in Provincetown or Wellfleet, when friends were kind enough to take us there in cars—or lend their cars to us. (Have you ever wondered if people read Shakespeare for fun? That used to be us, sitting by the fire, arguing over who got to be King Lear and who had to take on all three daughters.) Lighter entertainment came through the TV we had, which was one of those wood-encased models on wheels (the wood would later catch fire) coupled to a VCR. If we walked for two miles in the opposite direction of the Superette, we could reach the Video Empire, which, despite the grand scale implied by its name, was actually a tiny little rental shop in a four-store strip mall. This is where we encountered the BBC renditions of Sherlock Holmes with Jeremy Brett, and considered ourselves cultured. But on the nights when we didn’t have the energy to pedal to the rental place, we could always pick up one snowy channel whose signal somehow made its way across Cape Cod Bay from Boston. This is how we discovered Judge Judy, as well as a particularly egregious TV adaptation of Conan the Barbarian. Pickings were slim. So other nights we just watched our bootleg recording of Young Frankenstein, which eventually caught fire.

But now look at us. We live in a small house in an isolated Cape Cod town. Well, that hasn’t really hasn’t changed. We have a car, too. But we drive it as little as possible thanks to the tremendous cost of gasoline and repair. So transportation hasn’t changed much either. Instead of the 1890s, we embrace the values of the 1930s. It’s a big step, even if we’re still completely out of our time.

But we’re connected. There are six computers in the house, and a few of them were manufactured just last decade. More importantly, we’ve got a router, and a broadband connection—and this changes life entirely. Now, we can purchase goods from around the world and have them delivered a couple days later. We can watch movies and television programs on demand. The answer to any question we have comes to us through our “Glowing Mother”, The Wife’s nickname for Google piped on to an LCD. We can follow political revolutions as they unfold, absorbing photos, videos, and reports delivered by citizen journalists and activists around the planet. We can know it all. And if anyone was listening, we could tell it all.

Yet I’m sitting here scratching away with a fountain pen, just as I was all those years ago. Is this the sign of some mental defect? An unwillingness to adapt? Or worse, could this be a sign of intransigence, resistance, incipient luddite revolutionism?

There was a banner in my High School gym that exhorted, “Lead, Follow, or Get Out Of The Way.” Whenever I saw this, I was happy to step to the sidelines, ignore the game, and hang out in my own little mental workshop. Don’t mind me, I’ll just be over here, not playing dodge ball. And I was always proud of this rejection. I could rebel by doing nothing. I was your modern day Thoreau.

But today—isn’t this what everyone is doing, with their tablets and their smart-phones? Today, isn’t it the crowd that’s tuning out the big game and plugging in to some kind of interior monologue?

Granted, they’re not alone. They’re texting, reading watching—communicating. But they’re taking themselves out of the local struggle and plugging into an echo-chamber of increasingly-fine-selected special interests. They’re skimming personal-tailored newsfeeds to reinforce their preconceptions and world views, just the way Dick Cheney insisted on having the TV in his hotel room pre-tuned to his precious Fox News. They are alone without being alone. They ignore the game and rebel, but they’re paying subscription fees to participate in the revolution.

I suppose this is what the free market is meant for. Every decision about where to spend our time and money is a sort of revolution, a rejection of what we’d supported before. A bigger market means more options, more chances for satisfaction. This keeps the money flowing, since a system with more options makes it more difficult for people to withdraw from the system entirely. The free market means you can disagree and still be welcome. So long as you spend money, you’re still one of us.

Even pirated music has to come across subscriber-supported lines. Even the pirate’s modem is plugged into electric utilities.

Even this fountain pen, with its gold nib—mined, no doubt, in some miserable hole by long-suffering hands—the use of such an object is a participation in a system, and represents my membership on the team of consumers. Come to think of it, I am on my last ink cartridge, and must soon head to the corporate store, or click Buy Now on the corporate website to acquire more. I’m not opting out. I’m paying in with everybody else.

But no. With this pen, there is some rebellion. It’s in the longevity. This pen has put down half a million words by now. It’s crossed out just as many. It was purchased once, as a token of love, and used hard for a decade and a half. I may have bought cartridge upon cartridge, but I’ve bought no other fountain pen in 15 years. And there’s a rebellion in this monogamy which just turns me on, somehow.