The Wife has some serious bad mojo on her computer - the sort where crudely formatted scripting windows pop up to ask for our bank account and routing numbers as well as her mother's maiden name. On top of that, the hard drive clicks away any time the ethernet cable is plugged in. When we unplug the Internet, the computer works for half an hour or so - then locks up.

Damn Microsoft Windows. I switched myself over to a Mac three years ago and then started messing around with Linux a year after that. I've never had any desire to go back. It's always been an unpleasant experience to sit down in front of a Windows PC and try to get anything done. Of course, the only time I ever do this is when I'm trying to fix a computer, so there's a slight bias to my perceptions. Regardless, the Windows user experience is staggeringly bad.

When I think about how much that PC cost (about $1000, three years ago) and what its predecessor cost (almost $4000, ten years ago), and when I think about how many hours I've spent trying to make the most out of these machines systems, tweaking for performance, digging problems out of the registry, running scans for viruses and spyware, backing up all the files and re-installing the entire operating system every couple of years when things get too bent out of shape (like now), just for the privilege of using machines that we spent a great deal of money for, I feel such a torrent of red-faced, hot-blooded physical rage that I need to close my eyes and slow my breathing before I damage the hardware in some primitive and physical way.

I can take some solace from the thought that not all that money has been wasted. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation does some wonderful work. They use their money to treat the problems and diseases that take the most lives, rather than tooting their own horn by tackling the most popular and glamorous causes. From this perspective, it seems that Microsoft has existed for the past few decades for the purpose of redistributing wealth from idiots, suckers, geeks and corporations to needy and sick populations. Looked at this way, you can almost admire them - even when you're one of the fleeced.

The Wife has not been able to share in my enthusiasm for Ubuntu, much to my dismay, as her computer faces every new virus and glitch. This is because she's built up her blog and website around a suite of tools which don't have clear analogues in Linux yet - or if they do, they have interfaces so different that she just can't be expected to learn the new tools and still have time to create website content and cook supper. Our 1998 copy of Photoshop (version 5.5!) fits her like a glove after years of use, so switching to GIMP, even if it's both a superior image editor and free to boot, just isn't an option. Then there's Dreamweaver, another substantial investment. Credit where credit's due: she laid out her site with frames and then dumped a whole forum inside it. I was telling her not to expect so much in such a short time, but once she got those online tutorials rolling there was no stopping her.

Still, I might prevail upon her, in time, to switch all those tools over to open source versions. After all, if she can learn how to use Dreamweaver from a couple of online tutorials, she should be able to make sense of Kompozer. Then, when there's an update to her software, she won't have to pay for it.

That leaves the stumbling block of Windows Live Writer, the tool she's been using to blog for the past year. Apparently it's the only thing in the world that lets you rant, offline, to your heart's content, drag and drop pictures wherever you please, and then make the post show up online in just the same way. I've been all over the internets looking for an alternative. No luck. All the Linux offline blog editors seem as buggy, quirky, and lacking in features as the rest of linux was a decade ago. Even the Mac alternatives to Live Writer, back when I was using the Mac as a Mac, seemed limited, lacking an easy way of inserting pictures and assigning posts to categories.

What's going on here? A blog editor has to be on somebody's list. Lots of folks are unwilling to give up on Windows now just because of this application. "Live Writer is the only thing I still need Windows for," is a common complaint.

Oh well. We'll take it when we can get it. All this software is free, after all, and since I lack the programming chops to contribute to open-source software, all I can do is evangelize and wait for it to fill the rest of my needs. And The Wife's needs.

In the meantime, this is what I'll do to woo her over. Now that her computer is so thoroughly skunked that only a complete overhaul will do, it gives me the opportunity to partition her drive. The stuff she needs to do in Windows can go in a small Windows partition. The software itself doesn't take up much room, when it comes down to it, so she'll still have plenty of space for pictures and documents.

The rest of her hard drive is getting set aside for the Ubuntu partition, where she'll fall in love with the simple but elegant interface, the menu full of free applications available for the trying, the lack of proprietary pre-installed crapware, and the freedom from running antivirus scans and worrying about spyware.

I'm hoping she'll do most of her web-browsing, downloading, and video-watching in Ubuntu. Eventually she'll get so sick of re-booting into Windows to write her blog posts that, by the time we do have a good Linux alternative to Live Writer, she'll be all too happy to just let the Windows partition go.

It feels a bit like I'm trying to get someone to eat their vegetables. "Open source is good for you. Try it; you might like it!" I guess that when you don't have kids, you start to play weird little games with each other. So what? It's more fun than arguing!

So here's hoping I can get The Wife's computer running again, and get her mind right on operating systems. Just don't tell her what I have in mind. It can be our little secret.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Do We Really Need More Writers?

It's with some trepidation that I ask this, since I've dreamed of making my living at the typewriter since I was, say, twelve years old. The crazy, next-to-impossibility of this goal only made it seem like something I'd have to work even harder at. My idealistic pursuit of literature was part of what made me attractive to The Wife, I dare say. (That and I was still able to nail Chopin's B-flat minor Scherzo back then.) Having secured The Wife, my literary output gradually trickled off. (As did my hours of piano practice.)

But as this blog shows, there are loves we can never fully forsake. I'm not so much a writer as a typist these days, and I know my limits, but I'll never stop laying down the words.

Still, I can't help agreeing with Ted Genoways, who writes over at Mother Jones about the looming death of the literary fiction magazines.

Key facts: "Back in the 1930s, magazines like the Yale Review or VQR saw maybe 500 submissions in a year; today, they receive more like 15,000." The article doesn't say what the circulation of the Yale Review is; the most recent figure I can google, from a 1991 New York Times article, is 4,000. Even if its circulation has grown four-fold in 20 years (a bet I'm not willing to take), it's an unhealthy publication that gets more submissions than subscriptions.

Genoways goes on to explain: "Graduates of creative writing programs are multiplying like tribbles. Last summer, Louis Menand tabulated that there were 822 creative writing programs. Consider this for a moment: If those programs admit even 5 to 10 new students per year, then they will cumulatively produce some 60,000 new writers in the coming decade."

He doesn't mention that universities will be raking in between six and twelve billion dollars doing it. And they're not really producing "new writers," are they? What they're producing are 60,000 new debt-laden MFAs ripe for disillusionment. Really, what are all those kids going to do? Maybe three or four of them can make a living writing novels. A few might have a whack at screen-writing, editing, publishing, or advertising. Some might step into the higher education pyramid scheme and teach the next generation of MFAs. (There's not much hope there, either, it turns out.) Just how are they expecting to pay back those student loans?

If every one of those graduates published only one book in the coming years, it would just about double the inventory of your local Barnes and Noble. I don't know about you, but I only plan on get through half of the books in there right now. (At least some of those MFAs will be writing poetry, though, so some of the new books will be slim.)

What's really heartbreaking is that, as much of a long-shot as a writing career is, you don't need any kind of degree to have your manuscript considered. Just mail it in; then, when it comes back, mail it in to someone else. This is one of the few careers that has a level playing field. It just happens to be sky-high.

But as this blog shows, there are loves we can never fully forsake. I'm not so much a writer as a typist these days, and I know my limits, but I'll never stop laying down the words.

Still, I can't help agreeing with Ted Genoways, who writes over at Mother Jones about the looming death of the literary fiction magazines.

Key facts: "Back in the 1930s, magazines like the Yale Review or VQR saw maybe 500 submissions in a year; today, they receive more like 15,000." The article doesn't say what the circulation of the Yale Review is; the most recent figure I can google, from a 1991 New York Times article, is 4,000. Even if its circulation has grown four-fold in 20 years (a bet I'm not willing to take), it's an unhealthy publication that gets more submissions than subscriptions.

Genoways goes on to explain: "Graduates of creative writing programs are multiplying like tribbles. Last summer, Louis Menand tabulated that there were 822 creative writing programs. Consider this for a moment: If those programs admit even 5 to 10 new students per year, then they will cumulatively produce some 60,000 new writers in the coming decade."

He doesn't mention that universities will be raking in between six and twelve billion dollars doing it. And they're not really producing "new writers," are they? What they're producing are 60,000 new debt-laden MFAs ripe for disillusionment. Really, what are all those kids going to do? Maybe three or four of them can make a living writing novels. A few might have a whack at screen-writing, editing, publishing, or advertising. Some might step into the higher education pyramid scheme and teach the next generation of MFAs. (There's not much hope there, either, it turns out.) Just how are they expecting to pay back those student loans?

If every one of those graduates published only one book in the coming years, it would just about double the inventory of your local Barnes and Noble. I don't know about you, but I only plan on get through half of the books in there right now. (At least some of those MFAs will be writing poetry, though, so some of the new books will be slim.)

What's really heartbreaking is that, as much of a long-shot as a writing career is, you don't need any kind of degree to have your manuscript considered. Just mail it in; then, when it comes back, mail it in to someone else. This is one of the few careers that has a level playing field. It just happens to be sky-high.

Anonymous Comments Turned On

The Wife just let me know that folks haven't been able to post anonymous comments to this blog. Well, sorry about that. Apparently Blogger assumes we don't know how to be nice to each other.

Anonymous comments should be working now. If you still have trouble email me and let me know.

Anonymous comments should be working now. If you still have trouble email me and let me know.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Something Melville Wrote Just About Us

The mind's been a million miles away from blogging, what with work and family obligations the last couple of days.

Until something better arises from me, have another couple passages from Melville, this time from the short story I and my Chimney. It may cast some light on questons curious readers have had on the relationship between The Wife and I as she pursues her schemes and adventures. In fact these two paragraphs did such a tremendous job of forecasting our relationship that I spat my pipe onto the carpet in excitement to read them out loud to her.

Until something better arises from me, have another couple passages from Melville, this time from the short story I and my Chimney. It may cast some light on questons curious readers have had on the relationship between The Wife and I as she pursues her schemes and adventures. In fact these two paragraphs did such a tremendous job of forecasting our relationship that I spat my pipe onto the carpet in excitement to read them out loud to her.

If the doctrine be true, that in wedlock contraries attract, by how cogent a fatality must I have been drawn to my wife! While spicily impatient of present and past, like a glass of ginger-beer she overflows with her schemes; and, with like energy as she puts down her foot, puts down her preserves and her pickles, and lives with them in a continual future; or ever full of expectations both from time and space, is ever restless for newspapers, and ravenous for letters. Content with the years that are gone, taking no thought for the morrow, and looking for no new thing from any person or quarter whatever, I have not a single scheme or expectation on earth, save in unequal resistance of the undue encroachment of hers.The barn thing really happened to me, by the way. We have the structure in the back yard and the collection of power-tools to prove it.

....

She is desirous that, domestically, I should abdicate; that, renouncing further rule, like the venerable Charles V, I should retire into some sort of monastery. But indeed, the chimney excepted, I have little authority to lay down. By my wife's ingenious application of the principle that certain things belong of right to female jurisdiction, I find myself, through my easy compliances, insensibly stripped by degrees of one masculine prerogative after another. In a dream I go about my fields, a sort of lazy, happy-go-lucky, good-for-nothing, loafing old Lear. Only by some sudden revelation am I reminded who is over me; as year before last, one day seeing in one corner of the premises fresh deposits of mysterious boards and timbers, the oddity of the incident at length begat serious meditation. "Wife," said I, "whose boards and timbers are those I see near the orchard there? Do you know anything about them, wife? Who put them there? You know I do not like the neighbors to use my land that way, they should ask permission first."

She regarded me with a pitying smile.

"Why, old man, don't you know I am building a new barn? Didn't you know that, old man?"

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

The Shorter Herman Melville

As a means of building my attention and concentration back to the task of reading Moby Dick, inspired by this artist's ambition to illustrate every page of this ponderous work, I have been working my way through a volume of Melville's short stories, mostly written around 1855, and published, in this edition, in 1950, which having rested on various shelves and in various boxes, migrated through used bookstores and moving vans until divulging itself from our storage shed a few months ago during the reestablishment of my reading-room.

Now reading Melville, my own sentences grow tendentious in sympathetic echo.

Despite the effort of attention these stories require, they are marvels of lingering truth, speaking to archetypes of human experience and building up, through elaborate structure, this sense of kinship with the reader who, much in the way of a passenger who cannot understand the meaning of each dial, switch, lever, and pedal in a baroque airliner cockpit, nevertheless experiences the sum total of these mechanisms and the elaborately riveted shell that contains them as the uplifting, thrilling experience of flight, and no doubt lands in a location far removed from their departure, grateful and exhilirated.

Lots of these stories are timely, despite our 150 year remove. "Benito Cereno" suspensefully tells the story of a slave ship rebellion, touching on levels of hatred and moral ambiguity that illustrate the horrors and motives of modern terrorism. "Jimmy Rose" tells of how a succesful merchant and socialite survives when he falls upon hard times, after "Sudden and terrible reverses in business were made mortal by mad prodigality on all hands." (Kind of nice to be reminded that the financial troubles of this decade were not the first we've known.) "The Fiddler" addresses the problem of striking a balance between genius and simple worldly happiness, and speaks a great deal to my new approach to the piano.

There's "Bartleby", of course, --but of course you're already familiar with Bartleby, who when presented with the bureaucratic errand running he was hired to do, decides that he "would prefer not to."? This story was, by the way, the first encounter I've had in literature with the literal application of "red tape" around a bundle of documents.

So far the most appropriate and haunting passage has to do with fear-mongering and salesmanship, and strikes to the heart of our current mad "War on Terror." It comes from end of The Lightning-Rod Man, which I'll reproduce here without fear of ruining the story, since there's still so much pleasure to be had from reading the beginning, and then the end a second time.

It's a shame Moby Dick has overshadowed the rest of his works to the extent that most folks haven't heard of these. They are every bit as worth reading, (not to mention a good deal shorter) and surprisingly appropriate to modern experience.

Now reading Melville, my own sentences grow tendentious in sympathetic echo.

Despite the effort of attention these stories require, they are marvels of lingering truth, speaking to archetypes of human experience and building up, through elaborate structure, this sense of kinship with the reader who, much in the way of a passenger who cannot understand the meaning of each dial, switch, lever, and pedal in a baroque airliner cockpit, nevertheless experiences the sum total of these mechanisms and the elaborately riveted shell that contains them as the uplifting, thrilling experience of flight, and no doubt lands in a location far removed from their departure, grateful and exhilirated.

Lots of these stories are timely, despite our 150 year remove. "Benito Cereno" suspensefully tells the story of a slave ship rebellion, touching on levels of hatred and moral ambiguity that illustrate the horrors and motives of modern terrorism. "Jimmy Rose" tells of how a succesful merchant and socialite survives when he falls upon hard times, after "Sudden and terrible reverses in business were made mortal by mad prodigality on all hands." (Kind of nice to be reminded that the financial troubles of this decade were not the first we've known.) "The Fiddler" addresses the problem of striking a balance between genius and simple worldly happiness, and speaks a great deal to my new approach to the piano.

There's "Bartleby", of course, --but of course you're already familiar with Bartleby, who when presented with the bureaucratic errand running he was hired to do, decides that he "would prefer not to."? This story was, by the way, the first encounter I've had in literature with the literal application of "red tape" around a bundle of documents.

So far the most appropriate and haunting passage has to do with fear-mongering and salesmanship, and strikes to the heart of our current mad "War on Terror." It comes from end of The Lightning-Rod Man, which I'll reproduce here without fear of ruining the story, since there's still so much pleasure to be had from reading the beginning, and then the end a second time.

"You mere man who come here to put you and your pipestem between clay and sky, do you think that because you can strike a bit of green light from the Leyden jar, that you can thoroughly evert the supernal bolt? Your rod rusts, or breaks, and where are you? Who has empowered you, you Tetzel, to peddle round your indulgences from divine ordinations? The hairs of our heads are numbered, and the days of our lives. In thunder as in sunshine, I stand at ease in the hands of my God. False negotiator, away! See, the scroll of the storm is rolled back; the house in unharmed; and in the blue heavens I read in the rainbow, that the Diety will not, or purpose, make war on man's earth."

....But spite of my treatment, and spite of my dissuasive talk of him to my neighbors, the Lightning-rod man still dwells in the land; still travels in storm-time, and drives a brave trade with the fears of man.

It's a shame Moby Dick has overshadowed the rest of his works to the extent that most folks haven't heard of these. They are every bit as worth reading, (not to mention a good deal shorter) and surprisingly appropriate to modern experience.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Typewritten Past

"But the blots, Turkey," intimated I.

"True, --but, with submission, sir, behold these hairs! I am getting old. Surely, sir a blot or two of a warm afternoon is not to be severely urged against gray hairs. Old age--even if it blot the page--is honourable. With submission, sir, we both are getting old."

---Herman Melville, "Bartleby the Scrivener"What was it like, before the internet? I can barely remember it. But I was there.

When did I get old enough to say, "I was there"?

I've had this love for typewriters since back before typing was required, back when "keyboarding" class was for kids who needed to find their way around an Apple IIE and "Typing 1 through 4" were for women who wanted to sit in lobbies and wear skirts and take cigarette breaks where they tried to seduce their bosses. This was when I taught myself to type.

Because I played piano pretty well, and because I had intentions of writing several novels, I figured I could teach myself and avoid associations with geeks and secretaries. I took an old 1970s typing textbook and my Olympia desktop beheamoth and worked my way through February vacation. Not once did I talk to Mavis Beacon. But I got the basics down, and now if you put me in front of a well-serviced IBM Selectric I'll lay down 120 words a minute. (I'll do the same in front of a computer, but with less satisfying noise.)

* * *

My grandmother only had three stories. The first was about taking her Mercedes around the racetrack in Daytona, and I don't think it really happened. The second was about taking the controls of a Cessna airplane after her second husband blacked out. This was true. He suffers from vertigo and extremely bad manners. However you would assume from her telling that she actually landed the plane. If you dug for details you'd learn that she just descended a bit and kept it straight and level until he woke back up.

Her last story was about her typing teacher and her fingernails.

My grandmother was once as pretty and rich as she was shallow. She still looked elegant when she was older, but she'd lost her youthful looks and most of her money by the time I could know her. And part of those looks were some long and well-tended fingernails.

At the women's junior college, her typing teacher disapproved of long fingernails. She would threaten my grandmother: if she got anything less than a perfect score on her mid-term typing exam, she would force her to cut her fingernails off.

Can you guess the conclusion of the story? It was the same every time. "I got that perfect score, and my teacher couldn't have my nails." She was still a young woman when my grandfather died, and those nails may have helped her to attract that second husband, the one with the vertigo and the bad manners. And despite his faults she stuck with him until he killed her in a car crash that he walked away from.

So it goes.

* * *

About the typing, though: I always thought it was neat that my grandmother grew up in a world where one could take so much pride in doing such a common thing so well.

But then, it wasn't quite as common, at the time. Secretaries typed official documents, authors typed creative documents (when they didn't use secretaries) and the rest of the folks pecked along as well as they could when they had to. Or they didn't bother. It was only when I could put my grandmother's childhood in perspective that I realised what a trade typing must have been.

But then, it wasn't quite as common, at the time. Secretaries typed official documents, authors typed creative documents (when they didn't use secretaries) and the rest of the folks pecked along as well as they could when they had to. Or they didn't bother. It was only when I could put my grandmother's childhood in perspective that I realised what a trade typing must have been.

The keyboard-entered word is so common now that it seems cheap and tawdry compared to the words of past decades. Short, abbreviated text has become the norm. No more than 75 characters, please! And you can only display them in a few uniform fonts (not "typefaces, which sound lively and engaging; but "fonts," which sound more like curses, something you want to leave behind and be rid of) on tiny screens. Our universe is more granular now, now that we have made the move from atoms to bits. There's no room for quirks, dust, smudges, or smells on the LCD display of a smart-phone. There's no occasion for an attorney to bark at his scriveners, "The blots, Turkey!" nor to forgive a professional for having too much beer with lunch. One curses, instead, about the cost of a toner cartridge, fully aware that the manufacturer has no chance of hearing, and wouldn't listen if he could.

Before the internet a thought would have to rest on the page for a time before postmen carried it to a publisher and it became available to the world. It wasn't indexed electronically, and no one could use a trademarked term as a verb to search for it. There were proper channels for those who wanted to publish, and most of them would turn your fingers black.

This wasn't a better state of affairs, some pre-electronic Eden we should set out to reclaim. But the old ways did lead one to put a certain care and deliberation behind one's communications, which came across to the reader as respect and good manners.

When a typo on the final draft meant reproducing an entire page letter by letter, accuracy and care became well-ingrained habits.

When a typo on the final draft meant reproducing an entire page letter by letter, accuracy and care became well-ingrained habits.

Once my facility with the typewriter surpassed that of the pen, it was a great discovery that a sheet of carbon paper would allow me to both mail a letter and keep it too. To make a copy with no extra effort--Melville's scriveners would have swooned at such facility! (Or would they have despaired at pending unemployment.) Parsimony with my own words had led me to to feel I should hoard them--banking, perhaps, against some future blight of original thought, when for inspiration I might want to page through and rediscover the methods I once used to woo a high school sweetheart.

"You be careful with those notes you're always passing back and forth," the mother of one such sweetheart advised me. "You should realise that once you become famous and successful, all your juvenilia will be published and scrutinised in academic journals."

Flattering as it was to assume anyone would care, I came to find this an unhealthy attitude. One cannot live a satisfying life while feeling unduly concerned about the opinions of their biographer. Kids really should be passing long, impassioned, perhaps even erotic (so long as they are literate) missives to each other when they pass in the hallways. The possibilities for anticipation and savour are so far beyond what's possible with instant messages and "texts", that to compare the handwritten note to the text message would be like comparing lovemaking with pornography.

But one should not expect the handwritten note to last. Perhaps my originals are out there still in the attic shoeboxes of old friends and sweethearts. But the binder where I obsessively kept my carbons has long been mislaid in one move or another, and this is probably the first time that I have thought of it since high school.

Meanwhile the missive that you've sent from your phone to another's, or posted to Myspace or Facebook, has multiplied and copied and propagated across servers to live forever, annotating and incriminating. Or maybe it will degrade and disappear through bit-rot. No one will be sure until some lawyer or secret policeman has occasion to search for it.

And we wrote letters every day

Which were later thrown away

And God knows what we wrote, or what they said

But this is probably how they read

* musical interlude *

I left the letters behind

In the basement of the apartment building when we moved

For the mice to nibble on.

I wonder how long they lasted.

-- The Fiery Furnaces, "We Wrote Letters Every Day"

Rough draft:

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Recipe for the Perfect Day Off

I have too many interests.

This is my recipe for the ideal day off:

It's a testament to The Wife's powers that I'm able to get days like this as frequently as I do – with good eating and company thrown into the mix. Despite the isolating nature of our interests (she's in her office and her kitchen much of the day) it's really all time with the family. It's a small house, by which I mean just the right size for a childless couple, so even on different floors we're just a hollar away from each other.

It's also a testament to The Wife's patience, by the way, that I'm allowed to practice the piano so much. It can't be easy listening to the same Haydn sonata for months on end.

But as satisfying as it is to have so many sources of pleasure in one life, it also leaves one feeling consistently unsettled by this sense that, whatever I'm doing in this moment, maybe one of those other things might be even more satisfying. So getting myself to focus is a bit of a challenge. It's why I enjoy those hours with simple, mechanical things. One note at a time. One letter at a time. Pharmaceutical companies would suggest I have attention deficit disorder, no doubt, and prescribe some Dexedrine. And I'd tell them to stay the hell out of my head. And to leave the kids alone, too.

Looked at from a different angle, attention deficit disorder is rather a preponderance of joy. What it really does is make one value the preciousness of time.

What I really can't understand is how anyone on this marvelous planet can spend four to six hours a day watching television, or squander a day shopping at the mall. "Really?" I say to them. "This day, this moment, this all that you are in the world right now, and this is the best you can come up with?"

This is my recipe for the ideal day off:

- 2 hours piano practice

- 2 hours reading

about an hour for a leisurely walk and a pipe

- 1 hour for a nap

- 2 hours writing on an old manual typewriter (focused and distraction-free)

- 1 hour for blogging

another 2 – 3 hours for fiddling around with the computers, reading news and blogs, and blogging

- Whatever's left before bed for a movie, games, & time with the family.

It's a testament to The Wife's powers that I'm able to get days like this as frequently as I do – with good eating and company thrown into the mix. Despite the isolating nature of our interests (she's in her office and her kitchen much of the day) it's really all time with the family. It's a small house, by which I mean just the right size for a childless couple, so even on different floors we're just a hollar away from each other.

It's also a testament to The Wife's patience, by the way, that I'm allowed to practice the piano so much. It can't be easy listening to the same Haydn sonata for months on end.

But as satisfying as it is to have so many sources of pleasure in one life, it also leaves one feeling consistently unsettled by this sense that, whatever I'm doing in this moment, maybe one of those other things might be even more satisfying. So getting myself to focus is a bit of a challenge. It's why I enjoy those hours with simple, mechanical things. One note at a time. One letter at a time. Pharmaceutical companies would suggest I have attention deficit disorder, no doubt, and prescribe some Dexedrine. And I'd tell them to stay the hell out of my head. And to leave the kids alone, too.

Looked at from a different angle, attention deficit disorder is rather a preponderance of joy. What it really does is make one value the preciousness of time.

What I really can't understand is how anyone on this marvelous planet can spend four to six hours a day watching television, or squander a day shopping at the mall. "Really?" I say to them. "This day, this moment, this all that you are in the world right now, and this is the best you can come up with?"

Saturday, January 16, 2010

Kids Today are More Depressed Than Ever Before; My Solution

Here's something that's sad, if not surprising:

More of today's US youth have serious mental health issues than previous generations.

To which I say:

More of today's US youth need to learn to dress with self-respect, forgo the advanced degree, learn a trade, smoke tobacco in moderation, enjoy the occasional drink, and view members of the opposite sex as treasures instead of conquests.

At least that's what worked for me. What they'll probably do is take a bunch more Prozac.

More of today's US youth have serious mental health issues than previous generations.

To which I say:

More of today's US youth need to learn to dress with self-respect, forgo the advanced degree, learn a trade, smoke tobacco in moderation, enjoy the occasional drink, and view members of the opposite sex as treasures instead of conquests.

At least that's what worked for me. What they'll probably do is take a bunch more Prozac.

Friday, January 15, 2010

A Mountain of Crumbs: A Memoir of Midcentury Soviet Chidhood

For a look at how things went down on the other side of the iron curtain during the second half of last century, check out this memoir: Elena Gorokhova's A Mountain of Crumbs.

It's a fairly gentle read. With the exception of a great-uncle who was shipped away to a gulag for telling a joke and whose fate haunts the story indirectly, there's no outright struggle here. No, this is more about growing up with the failures of communism and making do with less - not by choice, but by brutal necessity.

There's less wealth and goods, but less ideas too. This was a country where discussing the thoughts of foreigners could land you in prison. This was a country that enforced atheism, and tried to legislate love out of the marriage contract.

It's about the "game of lies" that pervades a nation when everyone is afraid to admit the truth: the government is broken, and it will destroy you if you bring this up.

Spoiler (from the dust jacket): she moves to the US as soon as she can.

It's nice to know that, whatever problems we had over here, our lives were still preferable to the alternative.

It's a fairly gentle read. With the exception of a great-uncle who was shipped away to a gulag for telling a joke and whose fate haunts the story indirectly, there's no outright struggle here. No, this is more about growing up with the failures of communism and making do with less - not by choice, but by brutal necessity.

There's less wealth and goods, but less ideas too. This was a country where discussing the thoughts of foreigners could land you in prison. This was a country that enforced atheism, and tried to legislate love out of the marriage contract.

It's about the "game of lies" that pervades a nation when everyone is afraid to admit the truth: the government is broken, and it will destroy you if you bring this up.

The rules are simple. They lie to us, we know they’re lying, they know we know they’re lying, but they keep lying anyway, and we keep pretending to believe them.After living through our own year 1955, it was fascinating to read how a woman born in 1956 in the USSR grew up in spite of, and because of, these restrictions.

Spoiler (from the dust jacket): she moves to the US as soon as she can.

It's nice to know that, whatever problems we had over here, our lives were still preferable to the alternative.

Thursday, January 14, 2010

The Long Term Consequences of Over-Exposing Ourselves on Facebook

I took all my information off of Facebook back in 2008, even before The Wife started her 1950s year. I didn't like the time-sink aspect of it. And when I'm going to share something of myself online, I want it to be something I've thought over, composed, and presented to my own standards. For some reason changing my status update several times a day to indicate how my digestion was working just wasn't what I was looking for in a communicative experience.

And here's why I'm glad I withdrew: an interview with an anonymous employee discussing how they store and profit from our data.

Meanwhile millionaire douche-bag and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg is off at the Crunchie awards telling his audience why privacy isn't a social norm any more. See, that's why it's okay for him to make millions off our friend requests and profile pictures. And that's why it's okay for us to flash all our most intimate details to the world over a medium that copies, duplicates, and never forgets.

I guess Zuckerberg doesn't have a problem with the British government monitoring every call and email passing through their country. Nor is he concerned with the fate of the thousands of political prisoners around the world who might like some control over their personal privacy and dignity.

Not that those political prisoners were arrested for broadcasting their views on Facebook or Myspace. But with friends like Zuckerberg eroding the social norms around our Reasonable Expectations of Privacy, it won't be much longer until governments and courts feel they have a legitimate right to know every little thing about us, and prosecute when they disagree. After all, why shouldn't the goons get to violate our dignity and search our homes without a warrant? We've already put all of that stuff up on Facebook years ago!

And here's why I'm glad I withdrew: an interview with an anonymous employee discussing how they store and profit from our data.

Meanwhile millionaire douche-bag and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg is off at the Crunchie awards telling his audience why privacy isn't a social norm any more. See, that's why it's okay for him to make millions off our friend requests and profile pictures. And that's why it's okay for us to flash all our most intimate details to the world over a medium that copies, duplicates, and never forgets.

I guess Zuckerberg doesn't have a problem with the British government monitoring every call and email passing through their country. Nor is he concerned with the fate of the thousands of political prisoners around the world who might like some control over their personal privacy and dignity.

Not that those political prisoners were arrested for broadcasting their views on Facebook or Myspace. But with friends like Zuckerberg eroding the social norms around our Reasonable Expectations of Privacy, it won't be much longer until governments and courts feel they have a legitimate right to know every little thing about us, and prosecute when they disagree. After all, why shouldn't the goons get to violate our dignity and search our homes without a warrant? We've already put all of that stuff up on Facebook years ago!

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Don't Throw Away That Old Computer - Put Ubuntu On It Instead

Much as I'd love one, I just can't afford a new computer right now. I've got a three year old Macbook and a two year old Asus Eee netbook, and then of course The Wife has that workhorse of a Dell desktop (also three years old) which she's been pounding her blog and website out on. So the fleet of tech is aging a bit, but that's no excuse to just up and buy more of it.

One thing I can afford to do is download the latest iteration of the Ubuntu operating system. It turns out that Ubuntu 9.10, "Karmic Koala," runs great on both my computers, which is a surprise. I thought the netbooks's screen was going to be too small to display properly, and Macs have always been notoriously tricky to get Linux running on, since the whole point of a Mac is to run that shiny, expensive operating system.

But the community of open-source developers have been working together on this problem long enough now that an installation of Ubuntu automatically detects the Mac's wireless card, speakers, touchpad, etc, etc, right out of the box. It installs in about half the time it would take to restore the Mac's original operating system, and as an added bonus takes up about a tenth of the space on the hard drive that Mac's OS X used, too.

The "Open Source" software community is a great example of a functional, modern-day community, pulling together to manufacture something for the greater good and the pure fun of it. Alas, I lack the skills to participate as a designer, programmer, or debugger. But it's been great watching Ubuntu and a few other flavors of Linux (Puppy Linux, Damn Small Linux, Xubuntu, Eeebuntu, Linux Mint) get improved upon over the last few years, to the point that this install seems to do everything I need, for free, and with more grace and elegance than the old Mac could muster on its own. (Granted, Apple's come out with a new iteration of their operating system, but if I wanted to play with that I'd have to shell out a couple hundred bucks. But I'm done paying for this computer.)

If you haven't tried out Ubuntu Linux, and you've got a computer that's a couple or eight years old, see if you can't get it up and running. Honestly, the install's super simple at this point, with the help of a couple of tutorials and the forums over at http://ubuntuforums.org/.

Once it's installed, this edition even has a link at the bottom of its "Applications" menu: Ubuntu Software Center. Open source applications have always been free, but now the installation of any office, graphics, internet, or video software is just a matter of reading through the menu and clicking what you want.

It's a great way to make more out of less and get a few more years out of that old machine. (Or to make your new one look exceptionally shiny!) Plus you'll soon discover how liberating it is not to worry about antivirus scans, firewall settings, and the other assorted prophylactics that are such a regular part of our online experience.

One thing I can afford to do is download the latest iteration of the Ubuntu operating system. It turns out that Ubuntu 9.10, "Karmic Koala," runs great on both my computers, which is a surprise. I thought the netbooks's screen was going to be too small to display properly, and Macs have always been notoriously tricky to get Linux running on, since the whole point of a Mac is to run that shiny, expensive operating system.

But the community of open-source developers have been working together on this problem long enough now that an installation of Ubuntu automatically detects the Mac's wireless card, speakers, touchpad, etc, etc, right out of the box. It installs in about half the time it would take to restore the Mac's original operating system, and as an added bonus takes up about a tenth of the space on the hard drive that Mac's OS X used, too.

The "Open Source" software community is a great example of a functional, modern-day community, pulling together to manufacture something for the greater good and the pure fun of it. Alas, I lack the skills to participate as a designer, programmer, or debugger. But it's been great watching Ubuntu and a few other flavors of Linux (Puppy Linux, Damn Small Linux, Xubuntu, Eeebuntu, Linux Mint) get improved upon over the last few years, to the point that this install seems to do everything I need, for free, and with more grace and elegance than the old Mac could muster on its own. (Granted, Apple's come out with a new iteration of their operating system, but if I wanted to play with that I'd have to shell out a couple hundred bucks. But I'm done paying for this computer.)

If you haven't tried out Ubuntu Linux, and you've got a computer that's a couple or eight years old, see if you can't get it up and running. Honestly, the install's super simple at this point, with the help of a couple of tutorials and the forums over at http://ubuntuforums.org/.

Once it's installed, this edition even has a link at the bottom of its "Applications" menu: Ubuntu Software Center. Open source applications have always been free, but now the installation of any office, graphics, internet, or video software is just a matter of reading through the menu and clicking what you want.

It's a great way to make more out of less and get a few more years out of that old machine. (Or to make your new one look exceptionally shiny!) Plus you'll soon discover how liberating it is not to worry about antivirus scans, firewall settings, and the other assorted prophylactics that are such a regular part of our online experience.

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Six Part Glenn Gould Interview on Youtube

Really need to get down to the piano tonight. Haven’t had the energy for practice on top of work and blogging, and I don’t want to lose the progress I’ve made in the past several months.

What a conundrum, huh: being beset by too many things that I love to do? If only we all had such problems!

Here’s another lovely problem: there’s more Glenn Gould videos on Youtube than I’ve got time for watching. I could really curl up for a Sunday or two and just absorb, the way your modern teenager could veg-out to a marathon of “100 best celebrity freakouts” on MTV. I think I’d get more pleasure out of my Sunday than this hypothetical teen. But all things in moderation. Even Gould.

I used to think Gould’s interpretations of Bach were slow and stodgy. Now I love the simple austerity of them.

Here’s the first of a six-part interview entitled “Glenn Gould Moments.” It looks like it was filmed in the 50s but I can't confirm. What do you think?

The whole series is worth watching. What a nut! He’s an early example of the self-absorbed eccentric, but I’ll forgive him that because what he makes is so perfect - even if he insists on the pretense of having one specific chair dragged around the concert circuit. He hasn’t given up the concert performances yet, as in later years he dedicated himself strictly to recording in studio. You get to see him interacting with the manager of the concert hall, picking out just which of the super-high end pianos are going to be right for him. And you get to hear some cutting comments about some of the “modern” music of that decade which has since faded into obscurity.

What a conundrum, huh: being beset by too many things that I love to do? If only we all had such problems!

Here’s another lovely problem: there’s more Glenn Gould videos on Youtube than I’ve got time for watching. I could really curl up for a Sunday or two and just absorb, the way your modern teenager could veg-out to a marathon of “100 best celebrity freakouts” on MTV. I think I’d get more pleasure out of my Sunday than this hypothetical teen. But all things in moderation. Even Gould.

I used to think Gould’s interpretations of Bach were slow and stodgy. Now I love the simple austerity of them.

Here’s the first of a six-part interview entitled “Glenn Gould Moments.” It looks like it was filmed in the 50s but I can't confirm. What do you think?

The whole series is worth watching. What a nut! He’s an early example of the self-absorbed eccentric, but I’ll forgive him that because what he makes is so perfect - even if he insists on the pretense of having one specific chair dragged around the concert circuit. He hasn’t given up the concert performances yet, as in later years he dedicated himself strictly to recording in studio. You get to see him interacting with the manager of the concert hall, picking out just which of the super-high end pianos are going to be right for him. And you get to hear some cutting comments about some of the “modern” music of that decade which has since faded into obscurity.

Monday, January 11, 2010

Fat Kids

Still time-tripping to the 1960's, over here.

Thanks to Boingboing for pointing out this three part documentary from the Wellcome Library that was produced to discuss obesity in children. Here's the first bit:

The "overweight" kids look perfectly normal by today's standards. The children I see in public (well, plenty of adults too, come to think of it) are either anorexic-model thin and trying to show off how sexy they are, or overweight beyond caring, draping their figures in formless sweats and baggy tee-shirts. Back then, though, and especially in England, it must have been shocking to see children ballooning to this size, after the privations and sacrifices of the war.

Funny, too, that the reason these kids are getting fat is their mothers are cooking too much irresistible food for them. It's so much easier to get fat now, when you don't need a mother - just a MacDonald's.

So much of the advice in this film seems common-sense today, in 2010: eat mostly protein because you need it to grow; avoid carbohydrates and sugars, make sure not to skip the vitamins. And just don't eat too damn much. It's like the doctor is pushing for a moderate version of the Atkins diet, without all the bullshit.

And much of it seems common-sense today, in 1956, as well. Folks aren't just born as "fat people", they have to eat to get that way. Yes, some folks have appetites that aren't balanced to their needs. They need to work to reign those in and eat reasonably. And don't forget to "take some exercise." These women may not have heard of calories, but any housewife capable of running a budget could understand how you get thinner by burning more energy than you take in. (Also, don't beat around the bush. Not calling the kid "fat" to his face isn't going to help him lose any weight.)

On the subject of nutrition at least, it's interesting to consider how the 1960s are the beginning of an era of madness. Folks had let go of the common sense of their parents but hadn't quite made things bad enough for their children that their children had started to figure out things on their own, realized they could sell this common sense by turning it into diet plans and gym memberships, and gotten rich.

I'll take the common sense of the past, by the way, since it isn't being sold to me by a celebrity on TV.

What other subjects have gone through a similar phase of madness, coming round today to another glimmer of reasonableness?

I'll nominate architecture, which the New Urbanists are starting to take back from Modernism.

Thanks to Boingboing for pointing out this three part documentary from the Wellcome Library that was produced to discuss obesity in children. Here's the first bit:

The "overweight" kids look perfectly normal by today's standards. The children I see in public (well, plenty of adults too, come to think of it) are either anorexic-model thin and trying to show off how sexy they are, or overweight beyond caring, draping their figures in formless sweats and baggy tee-shirts. Back then, though, and especially in England, it must have been shocking to see children ballooning to this size, after the privations and sacrifices of the war.

Funny, too, that the reason these kids are getting fat is their mothers are cooking too much irresistible food for them. It's so much easier to get fat now, when you don't need a mother - just a MacDonald's.

So much of the advice in this film seems common-sense today, in 2010: eat mostly protein because you need it to grow; avoid carbohydrates and sugars, make sure not to skip the vitamins. And just don't eat too damn much. It's like the doctor is pushing for a moderate version of the Atkins diet, without all the bullshit.

And much of it seems common-sense today, in 1956, as well. Folks aren't just born as "fat people", they have to eat to get that way. Yes, some folks have appetites that aren't balanced to their needs. They need to work to reign those in and eat reasonably. And don't forget to "take some exercise." These women may not have heard of calories, but any housewife capable of running a budget could understand how you get thinner by burning more energy than you take in. (Also, don't beat around the bush. Not calling the kid "fat" to his face isn't going to help him lose any weight.)

On the subject of nutrition at least, it's interesting to consider how the 1960s are the beginning of an era of madness. Folks had let go of the common sense of their parents but hadn't quite made things bad enough for their children that their children had started to figure out things on their own, realized they could sell this common sense by turning it into diet plans and gym memberships, and gotten rich.

I'll take the common sense of the past, by the way, since it isn't being sold to me by a celebrity on TV.

What other subjects have gone through a similar phase of madness, coming round today to another glimmer of reasonableness?

I'll nominate architecture, which the New Urbanists are starting to take back from Modernism.

Sunday, January 10, 2010

Smith Corona Galaxie Typewriter Mystery Solved

A Christmas typewriter brought a mystery. What is this key? I've never seen anything like it before. And when you press it, nothing seems to happen.

Moments later: "#@%&!"

Has this ever happened to you?

Now, one could just reach forward and push those keys back, straining the shoulder and risking ink-stained fingers.

Or one could follow a hunch (or read the manual) and try that key once we're deep in the well-charted territory of a key-jam.

Aha! Problem solved!

Moments later: "#@%&!"

Has this ever happened to you?

Now, one could just reach forward and push those keys back, straining the shoulder and risking ink-stained fingers.

Or one could follow a hunch (or read the manual) and try that key once we're deep in the well-charted territory of a key-jam.

Aha! Problem solved!

It works!

Saturday, January 9, 2010

Fahrenheit 451 and the Modesty of Vintage Nightmares

I'm gonna get a bit mod here and talk about the 1966 film adaptation of Fahrenhait 451. We caught the tail end of it on one of those classic film channels that doesn't play too many commercials and then afterwords talks about the movie for a few minutes. TCM, I think. Despite enjoying the book, I’d never caught the film before.

There's something lovely, stylish, and sleek about this vision of the future. Women in the 1960s were still exploring ways to be lovely, it seems, and the architecture, however misguided, held a sense of ambition and optimism.

But the cracks start to show through as well: the sterility of modern style, the tendency of sleek lines and concrete block construction to alternate between fascism and shabbiness.

Of course Truffaut was have been highlighting this angle, as he wanted to capture the bleakness of a future without books. Still, it's amazing how much his purposely dismal representation of dystopia mirrors the architectural mood around our local Community College (built in 1970).

It’s been a couple of decades since I read the book, but I recall the viewing room where Montag’s wife gave herself over to the idle consumption of television as being entirely walled in with television screens. The characters in the dramas that were broadcast became her family, and would share events with her in ways she could no longer interact with her flesh and blood friends and relations.

It sounded more like virtual reality than television. I’ve often wondered how Ray Bradbury felt about recent entertainments such as Second Life and World of Warcraft, since the world he depicted in Fahrenheit 451 seemed so prescient when one considers these new technologies. Back in the city we had a projector hooked to our computer that would display the contents of imaginary worlds across sixty square feet. (We had high ceilings.)

This is why I was shocked - shocked - the first time I actually saw a television depicted in the film. It’s tiny!

Look at that thing! It’s as if Truffaut, imagining this terrifying future in which people had given themselves over to shallow, mindless entertainments, couldn’t imagine a television grander than a modest flat-panel display available at Best Buy.

This was the spookiest part of the film for me: the realization that our brave new world contains technologies and temptations that make the grandest nightmares of 44 years ago look quaint.

On the upside, though, we’re still allowed to read anything we want. As long as our attention spans

There's something lovely, stylish, and sleek about this vision of the future. Women in the 1960s were still exploring ways to be lovely, it seems, and the architecture, however misguided, held a sense of ambition and optimism.

But the cracks start to show through as well: the sterility of modern style, the tendency of sleek lines and concrete block construction to alternate between fascism and shabbiness.

Of course Truffaut was have been highlighting this angle, as he wanted to capture the bleakness of a future without books. Still, it's amazing how much his purposely dismal representation of dystopia mirrors the architectural mood around our local Community College (built in 1970).

It’s been a couple of decades since I read the book, but I recall the viewing room where Montag’s wife gave herself over to the idle consumption of television as being entirely walled in with television screens. The characters in the dramas that were broadcast became her family, and would share events with her in ways she could no longer interact with her flesh and blood friends and relations.

It sounded more like virtual reality than television. I’ve often wondered how Ray Bradbury felt about recent entertainments such as Second Life and World of Warcraft, since the world he depicted in Fahrenheit 451 seemed so prescient when one considers these new technologies. Back in the city we had a projector hooked to our computer that would display the contents of imaginary worlds across sixty square feet. (We had high ceilings.)

This is why I was shocked - shocked - the first time I actually saw a television depicted in the film. It’s tiny!

Look at that thing! It’s as if Truffaut, imagining this terrifying future in which people had given themselves over to shallow, mindless entertainments, couldn’t imagine a television grander than a modest flat-panel display available at Best Buy.

This was the spookiest part of the film for me: the realization that our brave new world contains technologies and temptations that make the grandest nightmares of 44 years ago look quaint.

On the upside, though, we’re still allowed to read anything we want. As long as our attention spans

Friday, January 8, 2010

Debit or Credit

Why don't we all go back to cash instead and stop getting screwed? The New York Times has an interesting article on the way debit card processors charge us every time we swipe a card at the cash register.

The ascendancy of plastic over currency has driven me crazy for years. Let's look at what we gain by using debit and credit cards:

But seriously, if you told anyone in 1956 about those fees, what do you think he'd say to you? I'm sure it wouldn't be, "Hey, handing a full percentage of our country's wealth to just two corporations is a great idea! So long as it gets my grandchildren spending themselves stupid into debt!"

I understand the importance of banking, interest, and investment to the economy. Hell, I'm even grateful for the opportunity to pay the mortgage that let me purchase this house. There's a time and a place for interest, so I'm not going to go all biblical and say we should kick the moneylenders out of the temple.

But fer chrissakes can't we get this infernal plastic out of our wallets?

The ascendancy of plastic over currency has driven me crazy for years. Let's look at what we gain by using debit and credit cards:

- a little convenience (with debit cards)

- the chance to borrow money in an emergency (with credit cards)

- interest payments on an average household credit card debt of $8000,

- late fees,

- overdraft fees,

- service charges,

- risk of identity fraud,

- privacy - generating a permanent, searchable record of everything you've purchased,

- the loss of responsibility that comes from holding cash in your hand and only being able to spend what you have,

- processing fees! These are paid by the merchants. As consumers we're led to shrug them off. But they cost the merchant up to 3% of every transaction. The small businesses I've worked for (and the one we owned) paid by far the largest rates, since they lack the bargaining power to fight back against Visa and Mastercard. Given that over a third of transactions are processed with plastic, that means we're handing a whole 1% of the gross domestic product over to Visa and Mastercard just for processing our transactions.

But seriously, if you told anyone in 1956 about those fees, what do you think he'd say to you? I'm sure it wouldn't be, "Hey, handing a full percentage of our country's wealth to just two corporations is a great idea! So long as it gets my grandchildren spending themselves stupid into debt!"

I understand the importance of banking, interest, and investment to the economy. Hell, I'm even grateful for the opportunity to pay the mortgage that let me purchase this house. There's a time and a place for interest, so I'm not going to go all biblical and say we should kick the moneylenders out of the temple.

But fer chrissakes can't we get this infernal plastic out of our wallets?

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Ezra Brooks and Villa Lobos

Been busy with work and life the past couple of days. Saw some dear, long absent friends. Played with a two year old child. If we could be guaranteed a baby this happy, we might consider getting one ourselves. But of course there are no guarantees, and there a are a few more things we want to do first. (A very selfish and modern view, no doubt.)

Relaxing with a scotch and water and thinking I might get a post up before the end of the day. There are a handful of minutes left!

Here is my prescription for the end of your work week, wherever that may fall. Ezra Brooks scotch, which is in the budget range but which comes a very close second to Dewars for smoothness, flavor, and drinkability. (I like adding just a splash of soda or tap water to open it up a bit.)

And some music by Heitor Villa-Lobos, a modern composer whose career was coming to an end in the 1950s. Plug him into your pandora radio station (you’ll get mostly guitar solos) or search for performances of his piano works on youtube. More on him later, but until then, wonder why more folks don’t know about this music, and consider this my gift to you.

Relaxing with a scotch and water and thinking I might get a post up before the end of the day. There are a handful of minutes left!

Here is my prescription for the end of your work week, wherever that may fall. Ezra Brooks scotch, which is in the budget range but which comes a very close second to Dewars for smoothness, flavor, and drinkability. (I like adding just a splash of soda or tap water to open it up a bit.)

And some music by Heitor Villa-Lobos, a modern composer whose career was coming to an end in the 1950s. Plug him into your pandora radio station (you’ll get mostly guitar solos) or search for performances of his piano works on youtube. More on him later, but until then, wonder why more folks don’t know about this music, and consider this my gift to you.

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

Isaac Asimov's Sideburns

Yesterday I came across a couple pictures of Isaac Asimov as I was writing my post about The Naked Sun. This picture is actually on the back of one of the vintage editions The Wife bought me. Taken sometime around 1952, I'd guess, he seems every bit the mid-century young gentleman.

It was the first time I'd seen him without his characteristic sideburns. Most folks are probably more familiar with the portrait below:

To which I say, man, what a neat looking old man.

I've tried the facial hair thing, and while it does lend a certain maturity and gravitas, it can't help but leave one looking scruffy and ill-groomed.

It surprises me that sideburns aren't more popular. You can use them to signal your masculinity, wisdom, and experience, and you can still kiss your wife without scratching up her face.

It was the first time I'd seen him without his characteristic sideburns. Most folks are probably more familiar with the portrait below:

To which I say, man, what a neat looking old man.

I've tried the facial hair thing, and while it does lend a certain maturity and gravitas, it can't help but leave one looking scruffy and ill-groomed.

It surprises me that sideburns aren't more popular. You can use them to signal your masculinity, wisdom, and experience, and you can still kiss your wife without scratching up her face.

Monday, January 4, 2010

Isaac Asimov's The Naked Sun

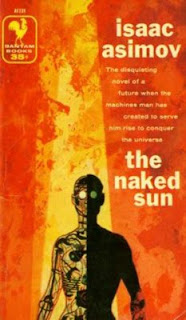

This year’s Christmas stocking was filled with a few mid-century golden era science fiction novels by Isaac Asimov. I hadn’t heard of any of these and had assumed they’d gone out of print, but a quick search on Amazon convinces me I’m mistaken: The Naked Sun, Pebble in the Sky, The Currents of Space.

It’s nice that folks are still buying and reading these books. There’s an implicit optimism in Asimov’s sci-fi which has gone around from exciting to quaint to imperialistic to gauche and has come back to just plain fun.

I just finished The Naked Sun, which, written in 1956, was the most recent of the three. It involves a plainclothes detective getting sent to the “outer planet” of Solaria to solve a murder - a crime unheard of on a planet with no want, 20,000 souls, and 200 million positronic robots.

SF was just starting to push into sociology at this point, so if it seems like Asimov is approaching his subject with big clumsy mittens on, it’s important to remember where he’s coming from. Earth: overpopulated to the point where people have to live in layers and layers of underground tunnels, so that they develop a pathologic fear of open spaces. The alien planet, Solaria: underpopulated and with so much robot labor available that people never see each other in person; rather they “view” each other with the aid of holographic cameras and projectors. Maintaining extensive estates with your robots is a point of such pride that physical contact with another human being becomes so taboo that it affects a physical response.

Oh my, how could someone commit a murder on a planet where folks can’t stand to be within a dozen meters of each other? Gosh, how are Earthmen who have become terrified of open spaces ever going to flourish in the galactic community again?

Oh my, how could someone commit a murder on a planet where folks can’t stand to be within a dozen meters of each other? Gosh, how are Earthmen who have become terrified of open spaces ever going to flourish in the galactic community again?

55 years on, we have to suspend an extra layer of disbelief - the disbelief that these would be the sorts of problems we’ll have in the distant future. We’re not going to worry about those singularity-driven artificial intelligences pulverizing the solar system into computronium. Terminators and Y2K? Nah. We’re all about psychological hang-ups and loopholes in the laws of robotics, up in the year four-thousand-some-odd. And we’re still running police departments from behind desks littered with papers while we smoke our pipes and cigars.

Unfortunately it’s impossible to read these books without seeing the flimsy cardboard props and painted backdrops of 1950s movie sets: the gritty underground governmental offices of an over-crowded Earth; the idyllic, robot tended estates of the sparsely populated outer planets. Except for the robots and the FTL rocket travel, Asimov doesn’t break the bank on special effects, here. The characters are all classic movie tropes too. There’s the hard-nosed but practical detective and the misunderstood widow-cum-murder suspect whose passions could never succumb to the sterile culture she was raised in. Strangely enough, the positronic robots, which are referred to as “boy,” by characters throughout the book, never seem to rise above the rank of scarcely noticed negroes. Spoiler: I kept waiting for their revolt, for the revelation that they were complex enough to be people just like us. But this isn’t the book for that kind of revelation.

I’m making all kinds of fun here. But I can’t help feeling that the reason all these tropes and cliches don’t ruin this little outer-space murder mystery is they’re effective. (“I can’t stand reading Shakespeare. There’s so many cliches!”) I mean, sure, all this stuff has been used before, right down to the mystery plot. But it hasn’t been used in space. And if our lives can carry on in space with the same sorts of drama that we’ve got going on here and now, well, then, maybe there’s a chance for us out there.

After all, who doesn’t like to think that human life will carry on outside our gravity well? And who doesn't want to own robots?

Fer Chrissakes, it’s 2010 already. I should own two.

Asimov wrote over 400 books, most of which are still in print, without ever dwelling on violence or more than hinting at sex. Diplomacy wins out over space battles and slimy alien pods, here. This is probably another reason why we feel compelled to make fun of him even while we can't stop buying his books.

It’s nice that folks are still buying and reading these books. There’s an implicit optimism in Asimov’s sci-fi which has gone around from exciting to quaint to imperialistic to gauche and has come back to just plain fun.

I just finished The Naked Sun, which, written in 1956, was the most recent of the three. It involves a plainclothes detective getting sent to the “outer planet” of Solaria to solve a murder - a crime unheard of on a planet with no want, 20,000 souls, and 200 million positronic robots.

SF was just starting to push into sociology at this point, so if it seems like Asimov is approaching his subject with big clumsy mittens on, it’s important to remember where he’s coming from. Earth: overpopulated to the point where people have to live in layers and layers of underground tunnels, so that they develop a pathologic fear of open spaces. The alien planet, Solaria: underpopulated and with so much robot labor available that people never see each other in person; rather they “view” each other with the aid of holographic cameras and projectors. Maintaining extensive estates with your robots is a point of such pride that physical contact with another human being becomes so taboo that it affects a physical response.

Oh my, how could someone commit a murder on a planet where folks can’t stand to be within a dozen meters of each other? Gosh, how are Earthmen who have become terrified of open spaces ever going to flourish in the galactic community again?

Oh my, how could someone commit a murder on a planet where folks can’t stand to be within a dozen meters of each other? Gosh, how are Earthmen who have become terrified of open spaces ever going to flourish in the galactic community again?55 years on, we have to suspend an extra layer of disbelief - the disbelief that these would be the sorts of problems we’ll have in the distant future. We’re not going to worry about those singularity-driven artificial intelligences pulverizing the solar system into computronium. Terminators and Y2K? Nah. We’re all about psychological hang-ups and loopholes in the laws of robotics, up in the year four-thousand-some-odd. And we’re still running police departments from behind desks littered with papers while we smoke our pipes and cigars.

Unfortunately it’s impossible to read these books without seeing the flimsy cardboard props and painted backdrops of 1950s movie sets: the gritty underground governmental offices of an over-crowded Earth; the idyllic, robot tended estates of the sparsely populated outer planets. Except for the robots and the FTL rocket travel, Asimov doesn’t break the bank on special effects, here. The characters are all classic movie tropes too. There’s the hard-nosed but practical detective and the misunderstood widow-cum-murder suspect whose passions could never succumb to the sterile culture she was raised in. Strangely enough, the positronic robots, which are referred to as “boy,” by characters throughout the book, never seem to rise above the rank of scarcely noticed negroes. Spoiler: I kept waiting for their revolt, for the revelation that they were complex enough to be people just like us. But this isn’t the book for that kind of revelation.

I’m making all kinds of fun here. But I can’t help feeling that the reason all these tropes and cliches don’t ruin this little outer-space murder mystery is they’re effective. (“I can’t stand reading Shakespeare. There’s so many cliches!”) I mean, sure, all this stuff has been used before, right down to the mystery plot. But it hasn’t been used in space. And if our lives can carry on in space with the same sorts of drama that we’ve got going on here and now, well, then, maybe there’s a chance for us out there.

After all, who doesn’t like to think that human life will carry on outside our gravity well? And who doesn't want to own robots?

Fer Chrissakes, it’s 2010 already. I should own two.

* * *

Asimov wrote over 400 books, most of which are still in print, without ever dwelling on violence or more than hinting at sex. Diplomacy wins out over space battles and slimy alien pods, here. This is probably another reason why we feel compelled to make fun of him even while we can't stop buying his books.

* * *

Is it me, or do genre book covers get progressively worse in later editions? The earliest cover (the one I have) hints at the themes of the book and leaves the rest to imagination. The second has nothing to do with the plot, but at least it titillates a bit - and titillation is something I can support (in moderation).

The last cover, from the 80s I would guess, hits you over the head with an ideological hammer. "Hmm, let's see. A man. I get that. A robot, that I can understand. A robot disguised as a man? Some kind of ambiguous cyborg? Is there a soul in there? Oh noes me circuits are blown!"

Not to mention that Asimov never even touched on themes of robot/human ambiguity in the book!

* * *

Oh hey - this paperback edition, which was printed in 1958, cost 35 cents. Which is about $2.75 in today's dollars. But last time I checked, a mass-market paperback at Barnes and Noble was around nine bucks.

What's up with that?

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Returning to the Piano

I’ve talked about how wonderful it is to be able to combine the best of yesterday and today in today’s world. One of the things I most love about the modern world are all the resources available for the budding classical musician.

Not that I’m budding. I’m too old for that. But now that we’ve moved back into the presence of the old grand piano, I find myself aspiring, musically, for the first time in years. This is a great surprise.

The aspirations are modest. I’m not shooting for scholarships or admission to Juilliard or even a high score from the piano teachers’ guild. I’m not expecting to perform in front of thousands (or even dozens) of people and I’m certainly not competing for a recording contract from Columbia records.

I used to hope for these things. In fact, back in the day, they seemed inevitable. It was simply a matter of applying ass to bench and shoveling hours of practice into the keyboard. My mom said I was the cleverest boy in the conservatory. (She also said I was the handsomest boy in school.) My teacher didn’t contradict her, so it seemed only natural that fame and fortune would come as a matter of course as the hours and years of practice accumulated.

A few things knocked me off course. Predictably. Piano skills were a wonderful tool for acquiring a high-school sweetheart, but once she was acquired, spending another weekend in front of the keyboard wasn’t as thrilling as, say, making out on a sofa. Meanwhile, none of my guy friends could be troubled to sit through a ten minute piece which I’d worked at for months. When none of your friends give a damn about the thing you love, it sort of punches a whole in your motivation.

Then I noticed that when I went to classical concerts I was usually the youngest member of the audience. Who would my audience be, I wondered, when I was the eccentric old bat up on stage?

I might have had more encouragement had I grown up in a city. Then again, there’d have been more competition, too. Even from Cape Cod, I was starting to realize how fiercely competitive a life in music would be. Less than 1% of Juilliard graduates make a living as performers. My teacher started to hint that a dual major from a place like Columbia might make more sense than a straight degree from a music-only school. “Not that you don’t have the talent to make it., but you’ve still got to look at the numbers.”

I thought, if I’m going to do this, I should really do it 100%. What’s the point of splitting my attention half-and-half with some other subject? I liked absolutes, as do most teenagers.